by Alain Cohn, Ernst Fehr, Michel André Maréchal from Nature 516, 86–89 (04 December 2014) doi:10.1038/nature13977

Trust in others’ honesty is a key component of the long-term performance of firms, industries, and even whole countries. However, in recent years, numerous scandals involving fraud have undermined confidence in the financial industry. Contemporary commentators have attributed these scandals to the financial sector’s business culture, but no scientific evidence supports this claim. Here we show that employees of a large, international bank behave, on average, honestly in a control condition. However, when their professional identity as bank employees is rendered salient, a significant proportion of them become dishonest. This effect is specific to bank employees because control experiments with employees from other industries and with students show that they do not become more dishonest when their professional identity or bank-related items are rendered salient. Our results thus suggest that the prevailing business culture in the banking industry weakens and undermines the honesty norm, implying that measures to re-establish an honest culture are very important.

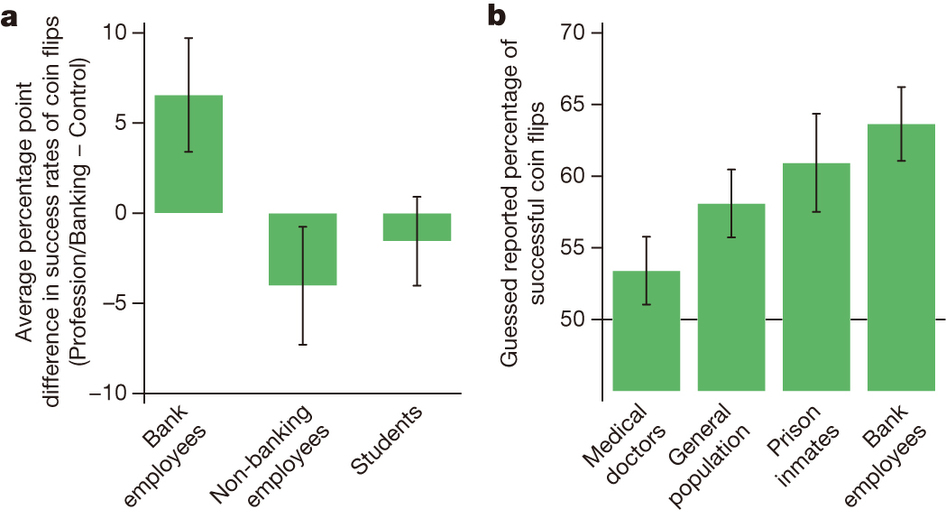

Our results suggest that the prevailing business culture in the banking industry favours dishonest behaviour and thus has contributed to the loss of the industry’s reputation. In contrast to their public image, however, we find that bank employees behave honestly on average in the control condition. To examine how bad bank employees’ reputation is, we asked people from the general population about the percentage of successful coin flips they would expect bank employees to report in the coin tossing task. Other survey participants were asked how physicians, prison inmates, or people from the general population would behave in this task. The participants believed that bank employees would be the most dishonest group; they believed that bank employees would report a rate of 64% successful coin flips, which corresponds to a cheating rate of 27%. This result, together with representative evidence from other sources, shows that the banking industry currently has a very bad reputation.

People’s confidence in the honesty of bank employees is a key asset for the long-term stability of the financial industry. Understanding the determinants of dishonest business practices is therefore essential for the development of possible remedies. Our results suggest that banks should encourage honest behaviours by changing the norms associated with their workers’ professional identity. For example, several experts and regulators have proposed that bank employees should take a professional oath analogous to the Hippocratic oath for physicians. Such an oath, supported by ethics training, could prompt bank employees to consider the impact of their behaviour on society rather than focusing on their own short-term benefits. A norm change also requires that companies remove financial incentives that reward employees for dishonest behaviours. In addition, existing research suggests that ethics reminders may promote compliance with the honesty norm. The use of ethics reminders requires a detailed analysis of work routines to find out where and when employees make critical decisions regarding norm obedience, so that normative demands can be rendered salient at the right time and place. These measures may be an important step towards fostering desirable and sustainable changes in business culture.